Key public schemes should have universal coverage rather than requiring bogus income certificates

Thomas Delaney

Vijay was distraught. He had racked up debts of Rs 30,000 running around various private hospitals, trying to save his wife, who had been reduced to skin and bones by TB meningitis.

Vijay, a mochi (cobbler) who earns less than Rs 200 per day, lives with his family of six in a shack by the side of a railway track. Despite his extreme poverty, he was unable to make an Aayushman card – the government scheme providing health insurance for up to Rs 5 lakh per household. The reason: his name was not on the official Below Poverty Line (BPL) list.

On another occasion I was assisting a senior citizen apply for the Old Age Pension, and had been told an income certificate was required.

“What income do you want to show on the certificate?” the babu asked me.

“I’ll check how much they earn.” I replied, pulling out my phone.

“No, no.” He shook his head, amused by my naivety. “What do you need the income certificate for? If it’s for a cancer card, it should be Rs 36,000 per year, whereas a ration card could be up to Rs 100,000. Just tell me what you need it for, and I’ll make it accordingly.”

Genuinely proving income is very difficult in a nation where some 90% of economic transactions are made in cash. Millions of destitute people are locked out of schemes that ostensibly target the poor because they lack the documentation to prove their poverty, and can’t pay middlemen to jump through all the bureaucratic hoops.

Meanwhile, some of the people who do access these schemes are relatively well off – having made income certificates that aren’t worth the paper they are written on.

Such abuse of schemes targeted to the poor are satirized in the film Hindi Medium, in which a wealthy couple, struggling to get their daughter admitted into an elite school, move into a slum in order to apply for the quota for ‘Economically Weaker Sections’ provided under the Right to Education Act (2009). In real life, the inclusion and exclusion errors of schemes targeted to the poor are no laughing matter.

Take the National Social Assistance Program (NSAP), which provides pensions to widows, senior citizens, and people with disabilities, as well as one-time payments to families whose breadwinners have passed away. NSAP provides valuable relief to some families, but there are mind-boggling levels of exclusion due to inability to provide the necessary documentation. For instance, there are some 55 million widows, of whom around 40 million would meet the economic criteria (annual household income under Rs 2 lakh) to entitle them to a pension – but only 8 million actually receive it.

Such schemes should be universalised. Granting pensions to all widows, senior citizens and people with disabilitieswithouta means test, would not only ensure that the marginalised are included, it would also drastically reduce inefficiency and corruption. The current system reeks of graft: for example, when an official does a house visit to verify the poverty of a widow, he routinely asks for ‘petrol money’. Making these schemes a universal right and streamlining the enrolment process – for instance, using the Aadhaar database to automatically enrol people for the senior citizen pension when they turn 60 – would greatly decrease the opportunity to demand bribes.

NSAP currently has 34 million pensioners and runs on a shoestring budget of Rs 96 billion. Back-of-the-envelope calculations based on Census data show that 80-85% of people with disabilities, senior citizens and widows are not on the pension. If properly universalised, the NSAP budget would need to increase by about Rs 500 billion.

One common argument against universalising public schemes is that it is too expensive to do so. An extra Rs 500 billion may sound like a lot, but it represents just 0.2% of GDP, and could easily be paid for in any number of ways. For instance, introducing an annual wealth tax of just 1% on India’s 166 dollar billionaires, whose wealth has skyrocketed over the last few years, would comfortably cover the bill.

A negligible sacrifice on the behalf of the wealthiest in Indian society could both drastically reduce inefficiencies and corruption and make a major difference in the lives of hundreds of millions of vulnerable people.

A pension of a few hundred rupees per month sounds like nothing to those of us who have a lot, but it means a lot to those who have nothing. For the widow who can afford a little more nutrition, for the grandfather who can get his glasses made, these small sums can enable a life of greater dignity and hope.

For the sake of millions like Vijay, it’s time to end the tragic irony of the poor being excluded from schemes that ostensibly target them. We need tobuild a more equitable society by providing key services for everyone.

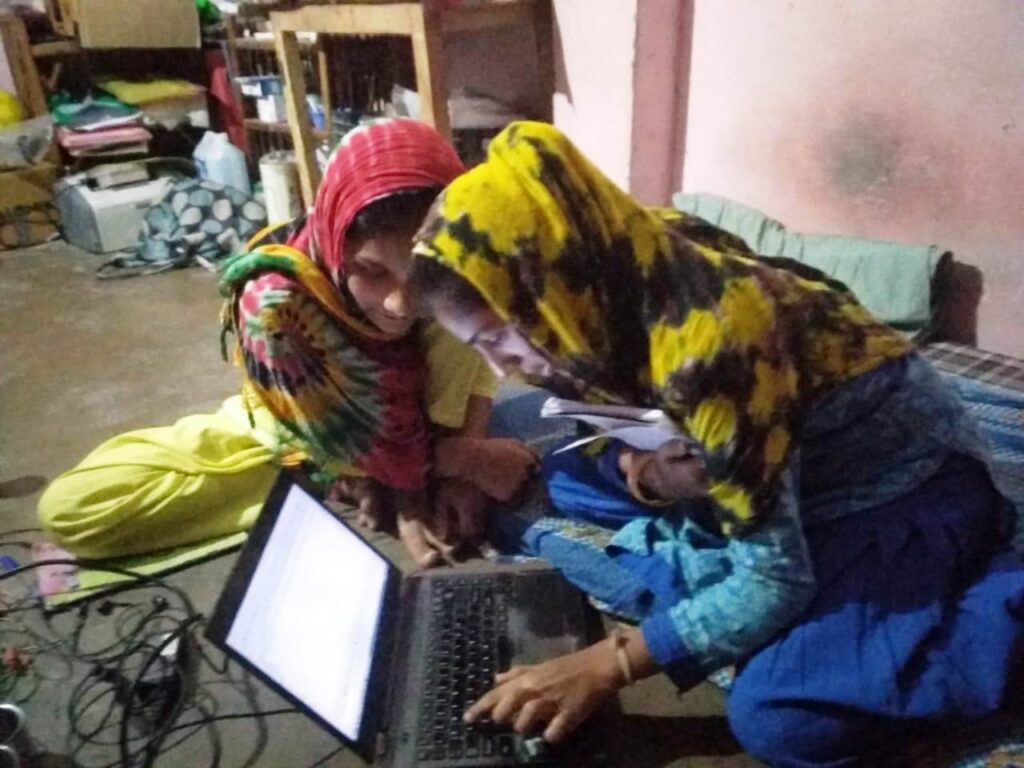

Thomas Delaney is a Lucknow-based literacy program trainer with a non-profit. He has worked for many years to assist people from slums get access to government services.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are the author’s own, and The Good Sight does not necessarily subscribe to them.